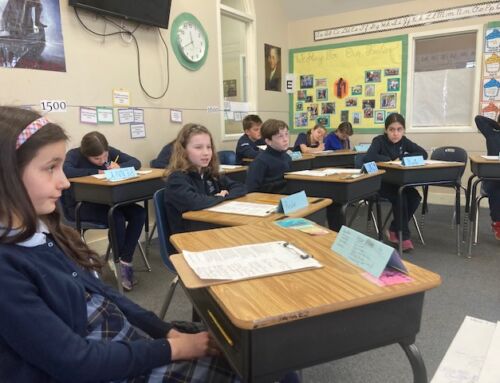

If you enter my second grade classroom at St. Benedict Classical Academy at noon any day, you would be amazed at the still and serene scene of my typically lively, high-spirited seven-year-old students. Sprawled comfortably around the room – nestled by our library nook, in the corner with pillows, or at their desks – and with their noses in books, each student is absorbed in the world of The Wind and the Willows, Magic Tree House, or Anne of Green Gables during our daily “quiet reading time.”

This past semester as I have read my own novels for my “Teaching the Novel” class in my graduate program, I have been transported back to the world that so often enthralled me as a seven-year-old– a world that pulled me in and swallowed me, where the life of Fern Arable became my life, and the problems of Laura Ingalls Wilder became my problems. It was a world where seven-year-old Gabrielle forgot everything around her and struggled through the Great Depression, survived the early colonial settlements, and explored the English countryside. The world that brings a hush over a group of seven-year-olds. The world that for a time becomes their world. The world that surrounds them. The world of the novel.

As my graduate school classmates and I have grappled to define ‘the novel’ over the past few months as we’ve read some of the greatest classics of authors like Jane Austen, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Herman Melville, I have been continuously amazed at the novel’s profound ability to immerse the reader in its world. A world that is both so recognizably like our own, and yet simultaneously causes us to forget ours completely. Jose Ortega Y Gasset, in “Notes on the Novel,” remarks that in order to enjoy a novel, “we must feel surrounded by it on all sides”1. Precisely because the novel is “preeminently realistic,” it is also incompatible with our outer reality, our own world. Because it is like our world, it is unlike our world, and it is an entirely new world. That is the beauty of the novel.

With young readers who are actively developing fluency and comprehension, we enter slowly into these worlds, a few chapters at a time. To teach them the novel and to teach it well, I must help cultivate their receptivity to immersion – an ability that, if you enter my classroom at mid-day, you will see is a natural faculty of young minds. I work to give my students “the tools” of immersion: narrating back recently read chapters, illustrating significant and favorite scenes, noticing small details, formulating questions and wonders.

Recently, I have been greatly inspired by Melville’s Moby Dick – an intricate and beautiful multi-form narrative, with encyclopedism, philosophy, play-like soliloquies, and oral stories that pull me deeper and deeper into the whalers’ world. At a classical school, such as St. Benedict Classical Academy, we have the wonderful opportunity to integrate content and curriculum across the subjects. Melville, who surrounded me with ‘the whale’ as he classified types of whales while philosophizing about them while on the hunt, has taught me to help my students become immersed in our novels with a similar multi-form approach. In the spring, as we study plants and insects in science, I cannot wait to compare insects with spiders, so that as we read Charlotte’s Web my students are reminded of their own world in a way that causes them to forget their world as they fall deeper into a new one: the world of the novel.

AUTHOR: Gabrielle Morris, First Grade Teacher

1Jose Ortega y Gasset, “Notes on the Novel,” (1925), in Michael McKeon, ed., Theory of the Novel: A Historical Approach (Johns Hopkins UP, 2000).